How Can I Make Useful Knowledge?

On trying to be useful with words

‘It is my practice at this hour to read some improving book; but, if you desire my services, this can easily be postponed, or, indeed, abandoned altogether.’ - Jeeves

In ‘The Inimitable Jeeves’, P.G. Wodehouse describes the daily shenanigans of Jeeves, a manservant of a stately Englishman. The Englishman, Bertie, is a bachelor amongst London’s upper crust. And Jeeves is a competent, fiercely loyal and witty employee that caters to his every whim. The two have an affectionate relationship; Jeeves’ tasks include elaborate schemes to fend off gold-digging suitors, doing calculations for horse racing bets, and generally procuring a odd items on demand. In return, he has ample free time and receives what seems to be a healthy salary.

In one story, Jeeves attracts hundreds of cats to Bertie’s apartment with rotten fish to fend off a potential suitor’s father - who was secretly known to have a cat allergy. But nothing escapes Jeeves, and yet again he managed to engineer a situation to gracefully save Bertie from a costly, unwanted romance.

Unsurprisingly, Jeeves’ skills draw admiration from Bertie, his employer, as well as the female employees of the other British aristocrats. But it is by far his intelligence of the social scene, and knowledge of the world that provides most value to Bertie. Jeeves is able to know things, to know many things, and to present such information in a way that was non-trivial to whom he served.

And so, these fictional stories of Jeeves made me reflect what it means to be truly useful with knowledge.

I think a big chunk of my peers in the workforce feel inklings what it means to truly add value through knowing things. Now that knowledge is cheap, a part of me feels replaceable, and at least once a day I ask myself of what value I’m adding through me writing and reading.

By far and large, I’ve been training my whole life to be useful in the realm of knowlege and theory. But now knowledge work feels less and less useful because there are less barriers to entry - you need a computer and some paper, and this is becoming more widely available. Moreover, more people have degrees (grade inflation), more people have internet (starlink), there are more people, and most relevant to us all, AI is getting better. There is a wide range of evidence that AI is getting better at coding than humans. The quality of AI literature review is also becoming excellent.

And I used to feel bad about this. After all, I want to be useful, if not for any other reason than a primal urge to maintain relevance in my community. And I think that the past three years have become especially poignant, with these feelings coming in the midst of tools like Claude code basically being able to do most tasks I ask it to, a psychological wave of people worried out about losing their jobs, and a general sense of lower societal trust amongst society.

But over the past few months, I feel like this has ailed me less. Because I now believe that it’s actually very hard to be useful in the ways that matter. But that doesn’t mean I should stop trying!

And so, what’s the point of being useful? And why is it so hard? I’ll try to explain why in this short note, and how I’m trying to be more useful by writing words on paper.

First, let’s take a quick step back and ask where we are in the state of the world. After the initial freakout I had after seeing LLMs doing literature review, and despite rapid advancements since then, I still think that the top 1% of human writers vastly outperform LLMs knowledge dissemination and writing. I’m specifically referring to non-fiction writers and the best bloggers who have written to audiences with wide appeal.

My evidence for this is anecdotal, but I still find reading paper books to be more insightful that just asking Claude or other LLMs questions. And this gives me evidence that humans can still be useful with ideas and words. Last year, here were some of my reads in non-fiction:

*Tuxedo Park: A Wall Street Tycoon and the Secret Palace of Science That Changed the Course of World War II* by Jennet Conant (2002)

*How to Win Friends and Influence People* by Dale Carnegie (1936)

The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life* by David Quammen (2018)

*Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs* by Michael T. Osterholm and Mark Olshaker (2017)

*How Life Works: A User’s Guide to the New Biology* by Philip Ball (2023)

*A History of Modern Britain* by Andrew Marr (2007)

*Empire of AI* by Karen Hao (2024)

*Airborne: The Hidden History of the Life We Breathe* by Carl Zimmer (2025)

So what makes this stuff actually good? I think it boils down to a few factors.

First, it’s the ability to collect an encyclopaedic amount of niche knowledge and high fidelity descriptions of detail about the world. Second, it’s knowing what is ‘naturally interesting’ to humans, and knowing tactically when to go into more detail. Third is the ability to offer an opinion on something, or give a moral judgement. In other words, the author has their own objective function about how to write about the world and we see the process they take to get there. And finally it’s writing in a way that is nice to read, with style.

And so far, from my experience in working with LLMs, I don’t think that AI has managed to get remotely close to the author’s that I’ve mentioned. But that being said, I don’t think it will be long till they do. And so, I want to figure out how I can retain an edge.

Let’s go through the first point specifically on collecting knowledge, since this is what we are most in competition with in AI.

First, I still think there is value in having sheer amounts of encyclopaedic knowledge in a topic obtained either through reading or through first hand experience.In Tuxedo Park, Conant goes through excruciating amounts of detail in Alfred Loomis’ life, including his fraught marriages, affairs, friendships and his science. A lot of this was obtained through first hand accounts and interviews with relatives. Similarly with Osterholm’s work, we get a step by step run-down of how top officials in the US Centre for Disease control’s methods in tracking down the Ebola crisis. In this case, their key selling value proposition is just sheer levels of godly detail that they offer to their audience.

This kind of almost encyclopaedic knowledge of a certain subject is what I think is great about modern blog writers of today. If you have time, I recommend you check out the writing of Gwern, Adam Tooze, John Baez, Tyler Cowan, Terence Tao and David Jordan. This level of detail seems to still currently be a gap for LLMs. And what makes John Baez’s blog really great? Well in this case, it’s just doing something really niche, and providing an excruciating amount of details knowledge.

So how am I trying to load up on detail?

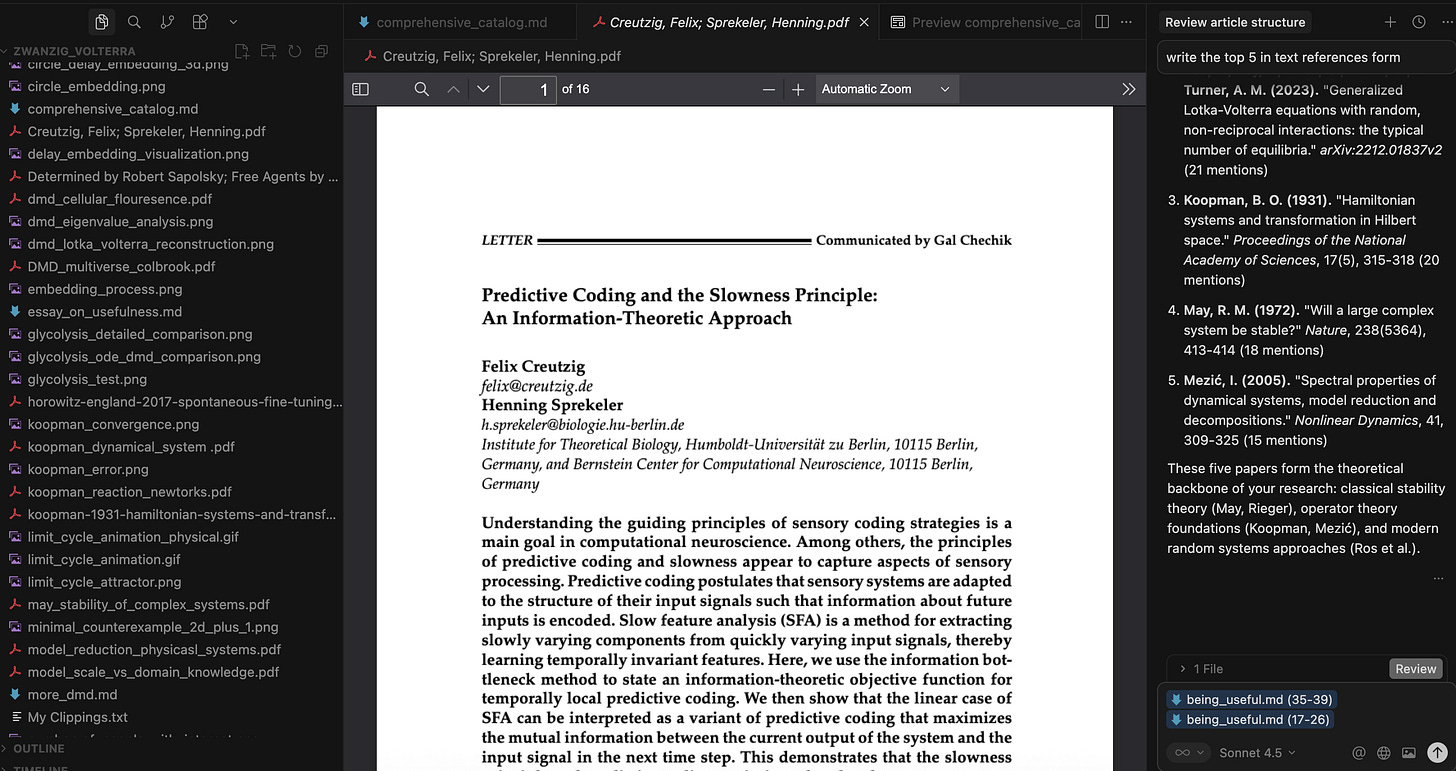

My main strategy is just trying to bulk up on how much I’ve been reading and how quickly I’ve been doing it. Volume is the lever I am pulling on, and for me this has meant just collecting way more pdfs of papers, organising them, and trying to extract details faster and more efficiently. I’m also reading paper books as well. As a guide, I’m trying to aim for the high tens of papers in my reading per question or topic I am exploring. I’m trying to also increase the volume and speed at which I’m going through papers. To find papers, I look at the references of a current paper I’m reading and then try to build a tree. I’ve found recording as many things things to be especially important. Previously I used to just read things, but now I’ve made it a habit to make hotkeys to save pdfs quickly in the places I want them to be saved. I then try to sort through the papers in Visual Studio code to make them easy to cycle through. I’ve also found my Kindle invaluable in highlighting quotes that I want to remember. I use Claude Code pretty judiciously to organise the content, and I’m trying to buy more storage to keep a record of things that I’ve read.

This is basically what my VS Code workspace looks like so far

For example, in my latest exploration in theoretical biology, I’ve started just keeping a big folder of different papers and models in one place where I collect models, notes and simulations. Here are some of the papers I’ve referenced the most in my recent articles on my blog

Rieger et al. - Lotka-Volterra stability analysis (25 mentions across documentation)

Ros, V., Roy, F., Biroli, G., Bunin, G., & Turner, A. M. (2023). “Generalized Lotka-Volterra equations with random, non-reciprocal interactions: the typical number of equilibria.” arXiv:2212.01837v2 (21 mentions)

Koopman, B. O. (1931). “Hamiltonian systems and transformation in Hilbert space.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 17(5), 315-318 (20 mentions)

May, R. M. (1972). “Will a large complex system be stable?” Nature, 238(5364), 413-414 (18 mentions)

Mezić, I. (2005). “Spectral properties of dynamical systems, model reduction and decompositions.” Nonlinear Dynamics, 41, 309-325 (15 mentions)

And so far, my process for developing a taste for what to write about has just been to ask myself questions that I myself find genuinely fun and interesting. Often this consists of prompting AI, asking friends, reading comments on my posts, or just pure whimsy. For example, one concept in dynamical systems is the theory of manifolds, which lead me down a rabbit hole in immersion theory.

And speaking of whimsicalness, I also think there is edge in reading old papers and old books - the stuff that the AI companies and data scrapers haven’t touched yet. You get an intuition about muddy things are at the start of an investigation and become braver in thinking about new ideas. When I read modern papers, I try to backtrack in time to when the seeds of the idea were planted to get an intuition about why the idea exists. My first old book that I read was on Rutherford. I started thinking about this when I signed up for an overpriced subscription at the London Library and looked at some relics from the 1800s. I found Rutherford’s first exposition of the atom, and tried to backtrack the history of electricity. One of the good things about London is that there are lots of old book stores with books that are unlikely to be used as AI training data, and so I try to pick up books for a bargain there.

In a way, I guess what I’m doing by reading a ton of papers is really just trying to curate good ‘word data’, for myself.

Another thing is also being much more ambitious about breadth of research. Taleb’s The Black Swan’ and Housel’s ‘The Psychology of Money’ convinced me of how the world’s economies are dominated by rare, extreme events. And I think this is true of research as well - most of our scientific research is dominated by a few amount of outlier ideas. And so the proper way to maximise the amount Black Swan ideas is by trying to read as widely as possible, from multiple angles.

I think another underrated way to get range is through interacting with the community. And so its worth trying to stay ahead of developments by being part of a community and speaking to as many people as possible. It’s for this reason (other than fulfilling friendships) that I try to hang out as much as possible with my scientist peers through dinners and events, to get a feel for what’s happening in scientific research. I myself have been hosting meetups and co-working sessions, which I’ll talk about in my next post.

I still have quite a few thoughts on disseminating knowledge in a useful way, but I feared that if I waited too long to write them that this post would run away from me! So stay tuned for more.

For all the reasons you’ve mentioned, I’ve started to lean into reading more fiction, as well as into writing fewer technical explainers and more articles with a perspective/take from me.

AI has shown tremendous progress in a number of fields, but it still has very poor taste when it comes to writing quality (with basically no improvement there over the last 1-2 years imo) and obviously cannot provide an idiosyncratic viewpoint from the perspective of someone we find compelling.

So focusing on writing creatively/well and writing from one’s own perspective and moral framework seems to be the niche we’ll settle into as AIs dominate more of the other parts of writing.

I found your workspace image very interesting. I would love to know more about how you've configured VS Code—which extensions you use, etc. I'm sure many others would find this valuable too.